Among the applications, the invention provides a sustainable alternative for microfluidic heat exchange, electrochemical analysis and electrical conduction

Text: Nayara Campos | Images: divulgação CNPEM

Researchers from the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) and the National Center for Research in Energy and Materials (CNPEM) have developed an innovative technology that allows the use of bamboo, a naturally insulating material, as an electrical conductor and microfluidic heater. The innovation represents a significant advance as it uses a natural and renewable resource as an alternative to conventional materials, making the process less costly and more sustainable.

The studies led by Omar Ginoble Pandoli, a researcher at PUC-Rio and the University of Genoa, Murilo Santhiago, a researcher at CNPEM in the area of nanotechnology, and Mathias Strauss, at the time a researcher at CNPEM, demonstrate that bamboo can be treated and modified to conduct heat and electricity efficiently, offering an innovative solution that combines thermal and electrical efficiency with reduced environmental impact, by replacing the use of metals and plastics for this purpose.

The conductive bamboo developed attracts significant attention for its potential use in architecture and electronics, as it is a potential substitute for electrical wires and pipes. With its resistance and conductive properties, the plant can replace traditional materials in various applications, contributing to the reduction of the industry’s environmental footprint and promoting respect for the environment, considering the advantages of sustainable use of the bamboo plant.

How the invention works

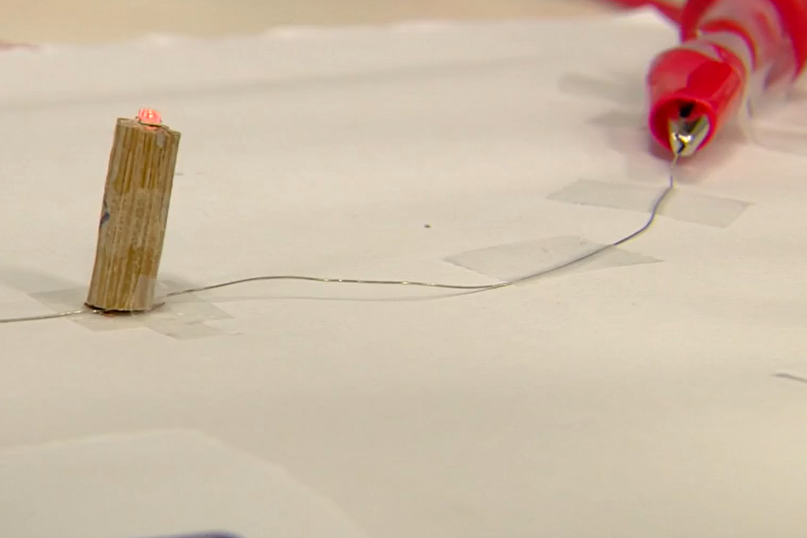

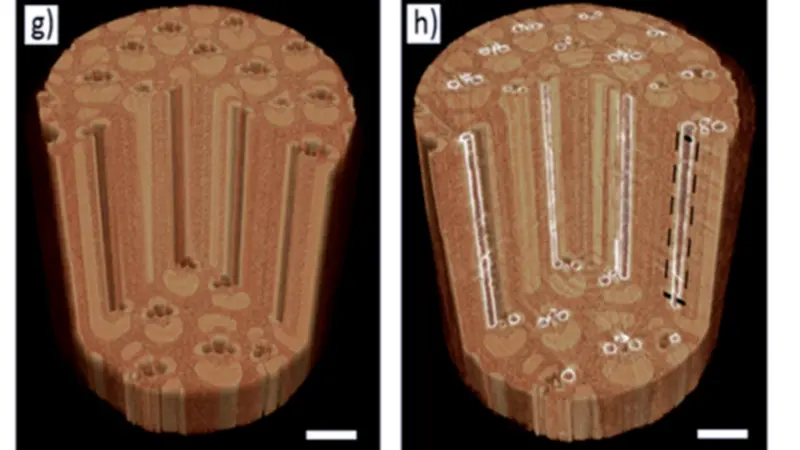

By coating the bamboo’s microchannels with silver-based metallic paint using a vacuum suction technique, the researchers obtained hollow conductive channels for the passage of gases, fluids and electricity.

X-ray showing bamboo in its natural state (left) and another with painted microchannels (right) | CNPEM press release

According to Pandoli, “bamboo is naturally an insulating plant and we turned it into a conductor by introducing a conductive paste inside the channels. From this, the bamboo became an electrical and electrochemical device,” explains the researcher. “Electrical because with the conductive paste a potential difference is applied, passing the current, and electrical circuits can be created to turn on led lights. Also, through the Joule effect, it is able to heat liquids such as water, which we used in the tests, in this case by obtaining a microfluidic heat exchanger. And electrochemical because we were able to isolate three portions of the bamboo in three different electrodes and this in electrochemistry can be used as a sensor to measure a chemical substance, making it an electrochemical sensor.”

For Santhiago, one of the advantages of the invention is that it uses the natural structure of the bamboo itself, without the need for adaptations. “We take advantage of the structure that nature has created, which are the microchannels, and it’s as if we were wiring inside the bamboo, but through an innovative process that dispenses with the wires and uses only a metallic paint,” he explains.

The researcher also points out that the fact that bamboo is a fast-growing plant makes the process even easier, since nature has the potential to create the plant and its microchannels more quickly than if it were necessary to produce them using microfabrication techniques, such as 3D printing, for example.

Bamboo’s potential for this application

Bamboo is an abundant plant in Brazil and, according to data from the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), the state of Acre is home to the largest bamboo forest in the world, covering seven million hectares. In addition, the rapid growth of the plant, which has around 200 different species in the country, makes it possible to scale the use of bamboo for industrial and commercial purposes without compromising this vegetation.

According to Pandoli, “the priority problem today is to think about what natural resources we can use. The idea of using plant masses is favorable because they are renewable, biodegradable and biocompatible sources, and bamboo among them is the fastest growing plant, with some species growing up to a meter a day,” he says. “So the scalability of devices built from bamboo is sustainable, because the biomass renews itself very quickly, unlike other trees.”

Another positive point highlighted by the researcher is that bamboo is a rhizome plant – a root that grows underground and sprouts to the surface – that the more it is pruned, the stronger it gets, unlike other plants that tend to die as they are cut, requiring a wait of years for it to grow again.

Next steps

With proven efficacy in laboratory tests, the researchers point out that the invention is available for partnerships in the industrial sector to check out the possibilities of producing the devices on a large scale. Pandoli also highlights the technology’s potential for educational use. “The invention could easily be used to disseminate science in schools, explaining how a heat exchanger or an electrochemical process works, because conventional electrodes are very expensive, costing around R$5,000,” he says.

The research was funded by the Carlos Chagas Filho Foundation for Research Support in the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ). With the help of the PUC-Rio Innovation Agency (AGI/PUC-Rio), the invention has a patent with the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) and is part of the portfolio of PUC-Rio patents available for licensing by the industrial sector.

Find out more about how to connect and license technology: https://www.agi.puc-rio.br/empresas

See other technologies available for licensing at the PUC-Rio Technology Showcase: https://www.agi.puc-rio.br/vitrine-tecnologica/